The gathering momentum of social isolation and loneliness

A new initiative to map the problem ecosystem

Image: Carlos Grury-Santos - Unsplash

Respecting the problem ecosystem

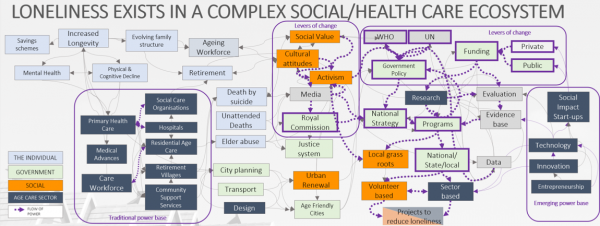

Social isolation and loneliness are gathering momentum as widespread social issues, so mapping the problem ecosystem is an essential part of determining appropriate programs of solutions. The very act of mapping the complexity and visualising it, is a challenge. One-off solutions to complex problems rarely work and in the case of social isolation and loneliness in older people, it will be programs of solutions, carefully considered, carefully matched and carefully codesigned that will produce effective results. The precursor to innovation is a culture of designing for participation within aged and community care. This culture produces appropriate solutions. Establishing and maintaining cultures of participation within local communities and the sector sets the scene for innovation. Within a participation culture, the opportunity to meaningfully address isolation and loneliness in older people becomes real. In order to do this successfully, the dynamics and all of the traditional and emerging players within the ecosystem need to be mapped.

Maintaining the status quo

The ecosystem has a diversity of players and there is no legally binding instrument to standardise and protect the rights of older persons within Human Rights Conventions. The establishment of a binding international convention is considered by some as a catalyst for the creation of a legal framework that defines the rights of older people. Decisional inertia within the international community and nationally leaves governments and communities without guidelines to drive change. National coalitions have formed to help create a unified voice and are made up of researchers, Not-for-Profit organisations and senior peak bodies. The funding for loneliness and social isolation is currently limited which leads to competition amongst research groups and duplication of work. Nationally agreed metrics of success are lacking which means that while interventions are ‘praiseworthy’, useful evaluation and benchmarking is impossible.

Image: The Loneliness Ecosystem - Matiu Bush

The future power dynamics

The changemakers emerging within this ecosystem are the next generation of older people who bring advocacy skills to their experience of ageing, unlike their predecessors. Political, environmental and gender-based activism have been prominent in the lives of those now turning 60 and 70. This shifts the power dynamic considerably.

Social impact start-ups and the role of technology such as wearables to detect loneliness can change power dynamics as data is made available in real time to older individuals, their families and friends. Start-ups in the aged and community care space are unencumbered by risk cultures that traditionally restrict innovation in larger aged care service providers. Better connections between the start-up community and the aged care sector will improve solutions offered by the start-ups as they will be more familiar with the most pressing problems facing the sector.

Understanding existing solutions efforts

There is wide acknowledgement in the literature that good social networks and the ability to sustain positive personal and social relationships are protective factors against loneliness. Australia is currently experiencing a surge of loneliness research, the establishment of the Australian Coalition to End Loneliness, a thriving social impact start-up community and a Royal Commission into Aged Care Services. These activities have culminated in an awareness of social isolation and loneliness in at both political and community levels. The result is that Government is now beginning to fund programs to reduce loneliness and social isolation in older people.

International research and evidence demonstrate that public health responses to ageing should reduce the impacts associated with older age, as well as focusing on resilience and psychological development. Healthy ageing is defined as ‘the process of developing and maintaining functional ability that enables wellbeing in older age’. This should occur in parallel with a focus on the age-friendliness of neighbourhood areas such as parks, local amenities, and opportunities for intentional neighbouring. Good design could and should influence social participation and general engagement in projects.

In the UK, a program of compassionate communities in Frome was launched to reduce isolation and loneliness in older people where the neighbourhood was activated through multiple projects, and GPs were encouraged to prescribe these initiatives for older residents at risk. The results were dramatic with a 14 percent reduction in emergency department presentations for older residents. This shows what’s possible when a neighbourhood is organised and committed to making the most of people’s ideas and strengths. It also shows that active neighbourhoods that are engaging older citizens in a range of activities result in older people being healthier. The keys to success are a participatory culture where everyone in the neighbourhood can engage, along with robust health metrics, enabled by long term strategic funding.

[Source: Matiu Bush, Deputy Director, The Health Transformation Lab, RMIT University, matiu.bush@rmit.edu.au]